A Very Perry Vinegar: Don’t Disregard The Pear

A proliferation of pear vinegars often pops up across the country when fall fades into winter. Whereas tart apples get turned into ciders, sauces, pies and preserves, the outlet for pears seems to be more limited with their mildly sweet and somewhat floral flavor profile. Often a little lemon is added to make pears shine in such applications — so why not turn them into a self-affirming acid themselves?

Often, commercially made “pear” vinegars are made by infusing apple cider vinegar with pear concentrate, resulting in something that’s more an amalgam of orchard fruit than a single variety. But a quality, artisan maker, like California’s Sparrow Lane will go full-bore pear. Its D’Anjou pear vinegar is juicy and lemon-lime bright, which I like to use reduced atop whipped ricotta, or spritzed upon a simple green salad. Farm to People, a farm to table delivery service in Brooklyn, NY, is selling quarts of Peachey’s organic pear vinegar from Millcreek, PA which has notes of honey and cinnamon spice. I was also recently turned on to the wonderful fruit of Subarashii Kudamono, which also produces an Asian Pear Vinegar from Pennsylvania-grown pears, with a delicate and fragrant acid compared to the d’anjou.

To make your own pear vinegar, it will take a little forethought, but In the past I’ve made a few fall-time perries (think apple cider, but made with pear), that I let double-ferment in barrel. I’ll even turn a batch into a sparkling perry vinegar, but adding some honey before bottle conditioning it for a year. Take that cap off, and you have an acid that glistens and glows, and adds a round, crisp softness, even for vinegar. It’s the perfect foil for holding onto fall.

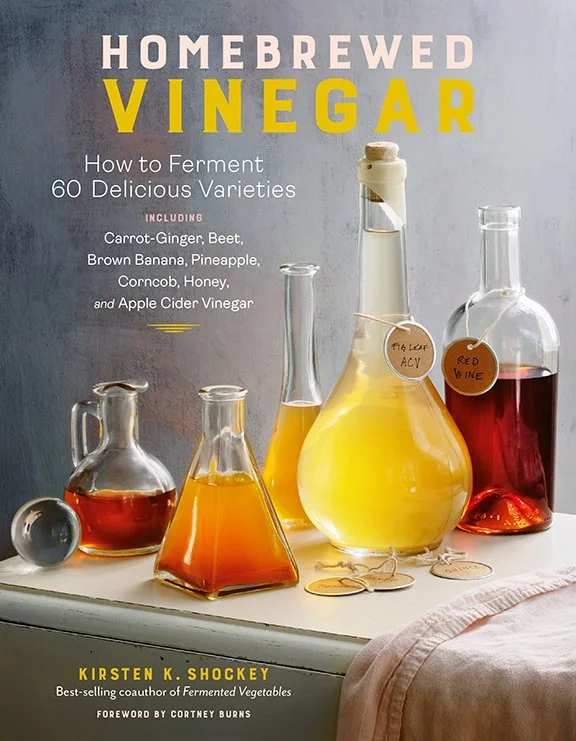

I fell for Kirsten Shockey’s version — an author, educator and founder of The Fermentation School, she shares my same penchant for pear vinegar, and has a Pear Pomace Vinegar recipe in her book: Homebrewed Vinegars.

“Pear vinegar is so great,” says Shockey. “That sorbitol coming through for the sweetness win.” Sorbitol, a sugar alcohol, also found in plums, is a smoother kind of sweetness than you’ll find in a higher amount of fructose found in apples. Shockey makes her own pear vinegar with fruit from the 80-year-old Seckel pear tree in her southern Oregon garden. “It’s still vigorous and well formed, producing hundreds of the sweet, small, rusty-red-blushed fruit this variety is known for,” says Shockey. The tree is the source of dried pears, pear butter and even pear crisps, but for Shockey, who’s been an avid cider maker for decades, it was a handful of years ago that she began making perries with the pomace, the pulpy residue after a pear is crushed and juiced. You can surely make pear vinegar with fresh juice too (I’d start with half juice, half water, and adjust from there to find the right sugar content), but be aware of what pears you’re using as they’ll all yield different results. Compared to Bartletts and Boscs, Shockey says Seckel pears are “supersharp tannic” when juiced.

Shockey uses the Apple Pomace Vinegar recipe in her book and omits the sugar, for a cleaner, sharper taste. Since it’s just pomace and water, “it’s a simultaneous fermentation,” says Shockey. “The yeasts will still turn the [natural] sugar into ethanol, while the acetobacters, dropped in with the addition of raw vinegar [to ensure acetic acid fermentation and prevent molding], will be waiting in the wings to get started”. “It was the best pear vinegar we’d ever tasted!,” Shockey admits.

Shockey loves pear vinegar in sparkling water as a tangy sipper. I like to dress a salad of bitter greens like radicchio, dandelion or escarole and caramelized nuts (e.g. walnuts, cashews, hazelnuts). The pea balances out all the roughage and sweet roastiness. It’s also great as a glaze on roasted root vegetables, or splashed in wine-poached pears for extra flavors.

Whereas The Twelve Days of Christmas begins with a partridge in a pear tree, your holiday season should end with pears in a bottle.

Pear Pomace Vinegar

Excerpted from Homebrewed Vinegar © 2021 by Kirsten K. Shockey, photography by Carmen Troesser, used with permission from Storey Publishing.

Yield 1 ½ quarts

1 pound (450g) pear pomace

2 quarts (1.9L) unchlorinated water, just off the boil

½ cup (118 mL) raw, unfiltered, unpasteurized vinegar, or a vinegar mother

Put the fruit into a sanitized half-gallon jar. Add 1 quart of the just-boiled water. Use the remaining hot water to fill the jar to the neck.

When the water cools to room temperature, add the raw vinegar. Stir well with a wooden spoon. Unlike with most ferments, you want to get some oxygen into the mix. However, make sure the fruit scraps themselves stay submerged; otherwise they can become a host for undesirable opportunistic bacteria.

Cover the jar with a piece of unbleached cotton (butter muslin or tightly woven cheesecloth), or a basket-style paper coffee filter. Secure with a string, a rubber band, or a threaded metal canning band. This is to keep out fruit flies.

Place on your counter or in another spot that is 75° to 86°F/25° to 30°C.

Stir with a wooden spoon once a day for the first 5 or 6 days. After that, stir now and then, if you remember. You may see bubbles: That is good.

The ferment will begin to slow down in about 2 weeks, at which point it’s time to take out the scraps. When you remove the cover, you may see a film developing on top. It is the beginning of the vinegar mother. Remove and set it aside while you’re straining out the fruit solids.

Line a strainer with a piece of butter muslin or fine-mesh cheesecloth and strain the mixture into a new sanitized jar. Press on the fruit and squeeze the cloth to get every last tasty drop out. Add the mother (if you have one) back into the jar and cover again.

Check the vinegar in a month, when you should have nice acidity. However, it may take an additional month or two to fully develop. Test the pH: It should be 4.0 or below.

Bottle the finished vinegar, saving the mother for another batch or sharing with a friend. Use immediately, or age to allow it to mellow and develop flavors.